The results are in for this year’s Iron Viz qualifiers, so I thought I could share some thoughts about the judging process, and of course about my involvement in it.

https://www.tableau.com/blog/top-10-qualifiers-iron-viz-2026

The judges for the Iron Viz qualifiers are about 30 volunteers from the current year’s cohort of Ambassadors and Visionaries, obviously not including those who are actually participating. This year I volunteered for the second time (previous was in 2024) – I can’t take part in any case because of the legal constraints that limit Iron Viz entrants to residents of only 32 countries in the world (more about that here), so judging is a good way to be involved.

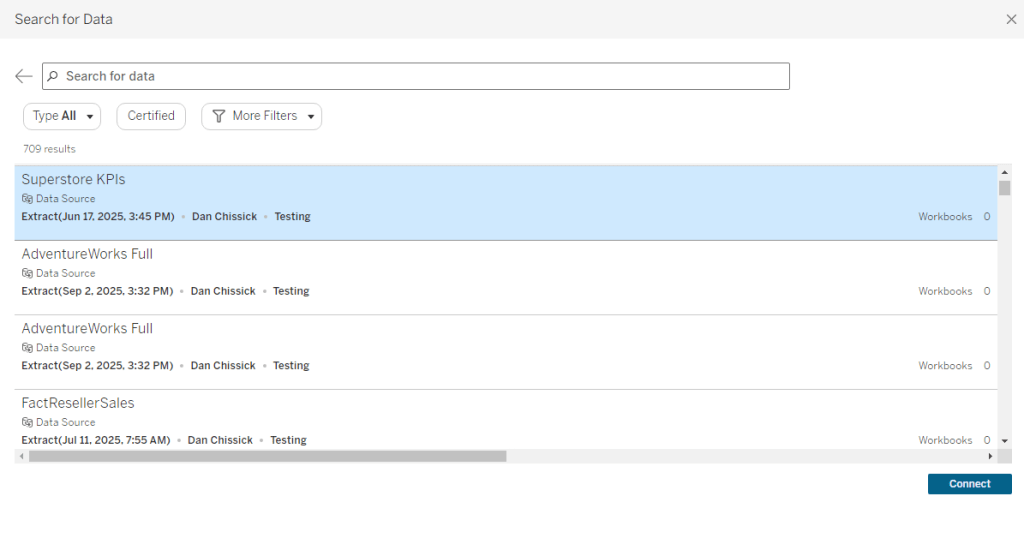

The vizzes are screened by the Tableau team to make sure that they comply to the minimal standards, such as the chosen theme (this year it was “Food and Drink”), and then each entry is assigned to 3 random judges. Many of the entrants publicize their work immediately after submitting, but we are asked to try and ignore the social media noise before judging, for obvious reasons. I was assigned 11 vizzes, but I had to decline one of them, as it was created by a colleague from my company and I had even given feedback on the content, so it was re-assigned to someone else.

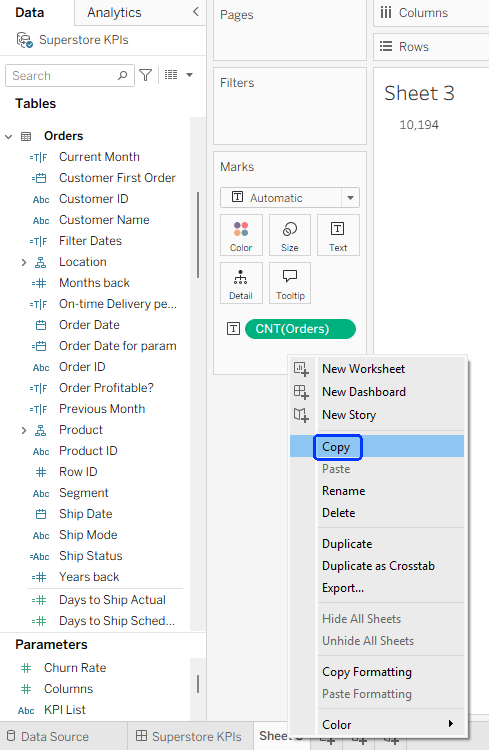

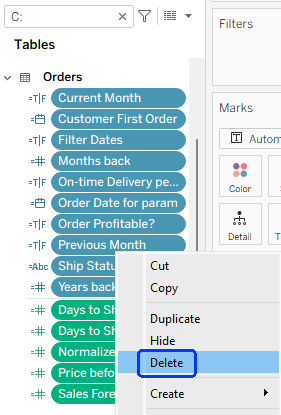

We had more than a month from receiving the anonymized vizzes until our deadline, so there was ample time. I invested at least half an hour on each – first investigating it as a viewer, then opening the workbook and seeing how it was created, including data sources, calculations, worksheet structure, and actions, and then assigning the scores and adding brief comments. When I had finished with all of them, before submitting all the scores into an online form, I also looked at the final ranking and evaluated if it reflected my general impression of the vizzes – because sometimes you can get immersed in the small details and scores, without seeing the big picture: which viz is the best?

I was impressed by the amount and variety of data collected by most of the participants. Most of the vizzes were based on multiple datasets with a wealth of data about their subject, and I’m sure a lot of effort went into collecting this data, before even starting on the design.

I have to note that most of the subjects did not interest me at all – I’m the total opposite of someone you would call a “foodie”, and I don’t drink almost anything except water. Some of the data, and even the food and drink names, could have been pure fiction, and I wouldn’t have known the difference.

I am not going to divulge any recognizable information about the vizzes that I judged, of course, only my general impressions. Overall, of the 10 vizzes, I would have said that one was of beginner level, 7 were good to very good, and two were outstanding.

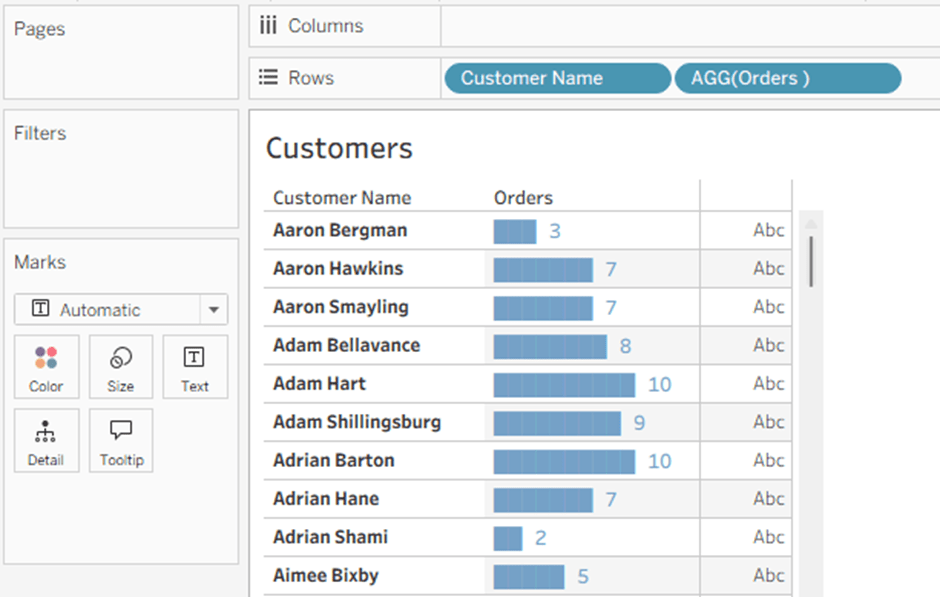

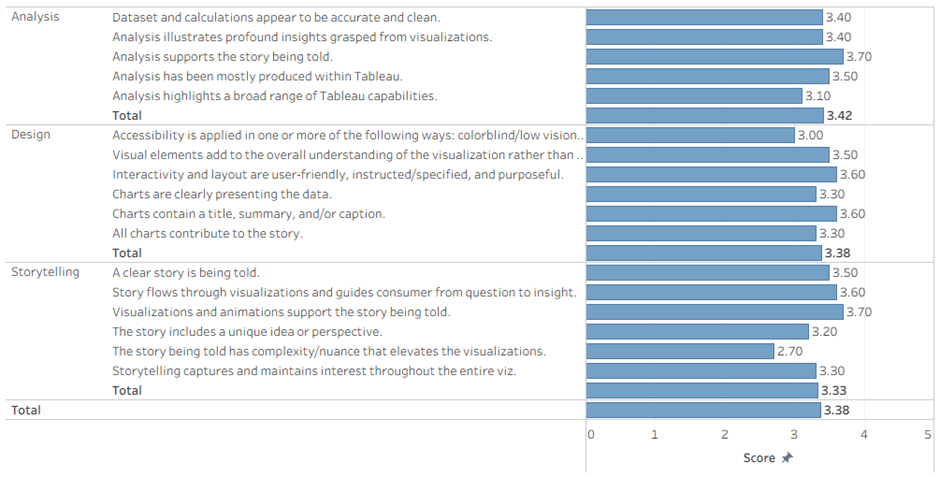

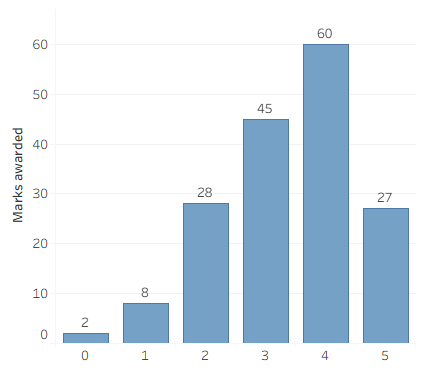

We judge all the vizzes by awarding scores from 0 to 5 on the well-publicized criteria: Analysis, Design, and Storytelling. This is what the scores that I awarded looked like:

Not much to be learned from this: most vizzes correlated well with their story, only the good ones had some complexity/nuance, and accessibility is not on everyone’s mind.

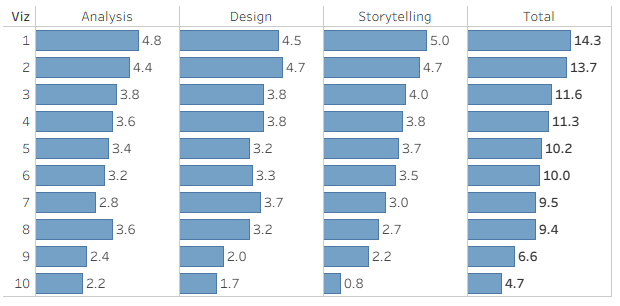

Another way of looking at it:

And the final results (anonymized Viz number), out of a maximum of 15 points:

My thoughts about some of the judging criteria:

Analysis

- Viz topic aligns with the contest theme.

- This one is obvious, and you don’t get a score for it – just True or you’re out.

- Dataset and calculations appear to be accurate and clean.

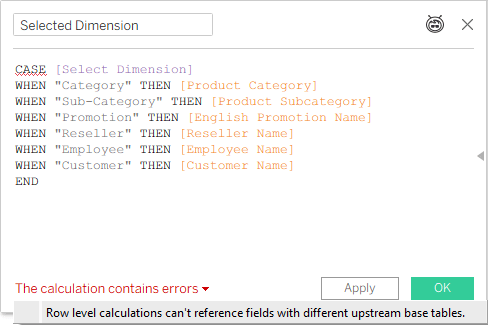

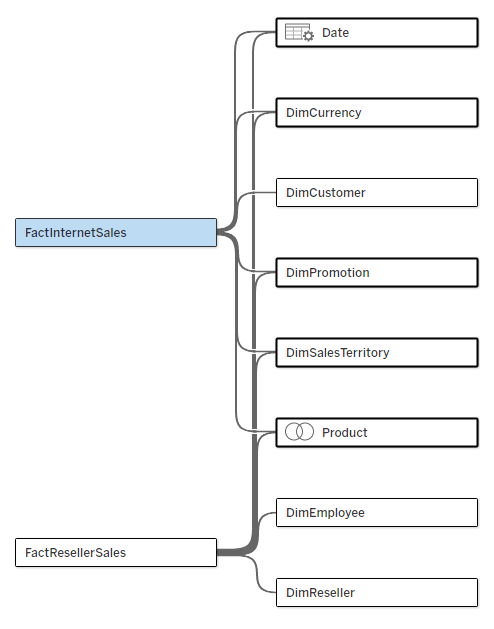

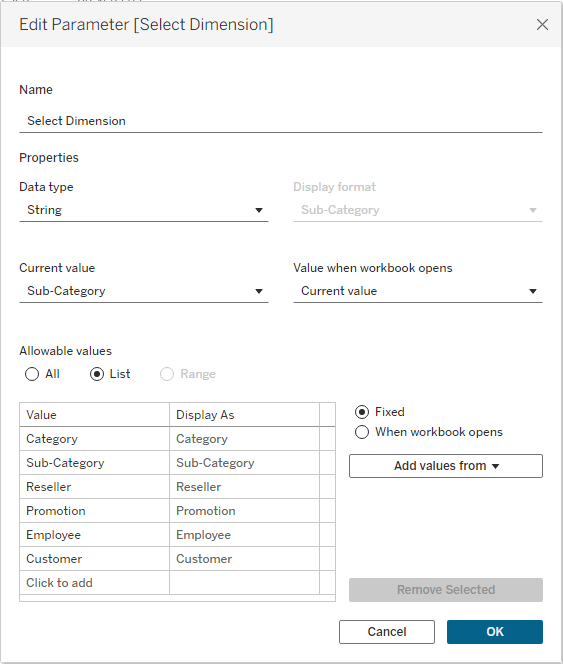

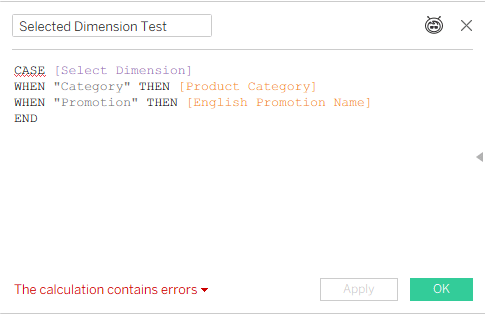

- This is where I check the data model: are there lots of data sources with disorganized names, or is there a nicely structured data model? And are the calculated fields well named and structured?

- Errors cost points here – if an action or calculation performs incorrectly.

- Analysis illustrates profound insights grasped from visualizations.

- Analysis supports the story being told.

- Analysis has been mostly produced within Tableau.

- I understand this as meaning that if you’re calculating aggregates in SQL, or bringing in coordinates for a Sankey chart from Excel, you’re not producing analysis in Tableau.

- Analysis highlights a broad range of Tableau capabilities.

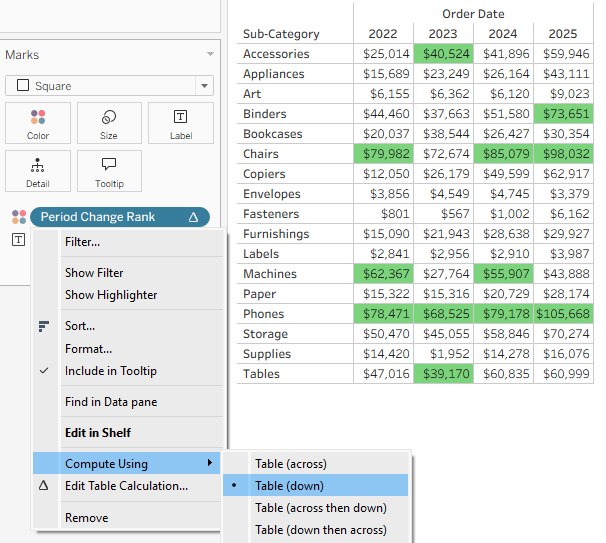

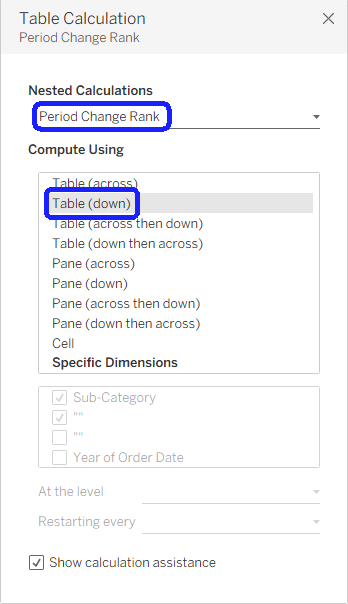

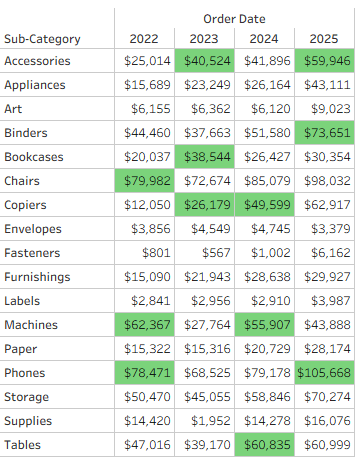

- Here is where I gave more points for using Tableau’s visual features: interesting chart types, dashboard actions, show/hide buttons, DZV, and even recursive parameter actions (my favorite, of course).

Design

- Accessibility is applied in one or more of the following ways: colorblind/low vision (contrast) friendly palette, limited use of images to convey text, font size 12pt or larger.

- I deducted points mainly for tiny fonts (there were lots of those), and a little for color palettes – it’s easy for me to judge, because I am slightly color blind.

- Visual elements add to the overall understanding of the visualization rather than distract.

- Don’t use charts if they don’t convey any information.

- Interactivity and layout are user-friendly, instructed/specified, and purposeful.

- Charts are clearly presenting the data.

- If I need to investigate a chart for more than a few seconds in order to understand it, you lose points.

- Charts contain a title, summary, and/or caption.

- All charts contribute to the story.

Storytelling

- A clear story is being told.

- Don’t just display data – you need to tell a story. Actually I’m not very good at this, but I can recognize a good story when I see one.

- Story flows through visualizations and guides consumer from question to insight.

- Visualizations and animations support the story being told.

- The story includes a unique idea or perspective.

- The story being told has complexity/nuance that elevates the visualizations.

- I looked for something special in the story: is it a bare analysis of the data, or are you investigating (or making me investigate) and discovering something?

- Storytelling captures and maintains interest throughout the entire viz.

- This is the easiest: was I captivated from the moment I first opened the viz, or did I lose interest at some point? The first impression was most important here.

So what about the results?

The viz that I ranked 3rd was in the top ten.

The viz that I ranked 2nd was in the top three, and qualified its creator to battle on stage in Iron Viz 2026.

And the viz that I ranked 1st …. nothing. Obviously two other judges didn’t like it as much as I did, or maybe Tableau have other considerations that also affect the final rankings.

Summary

Judging Iron Viz is quite a bit of work, but it’s one way for us Ambassadors to give back to the community. It definitely improves your critical thinking, challenges you to give constructive feedback, and of course it’s fun. Even the discussion within the closed forums among the judges is interesting. I’ll definitely do it again, if I have the opportunity, and huge thanks to Katy Clarke from Tableau who led the process and coordinated everything.